The winter time is our main class season when we host workshops every weekend. This brings a new group of attendees each week, most of which have never thought about making a knife before receiving a gift for the class during the holidays. Those that have thought about it and signed up on their own tend to have the "How hard can it be?" attitude. This is a reasonable thought considering that over the years we have taken hundreds of people through the knife making process. Experience levels range from professional metal or wood workers down to folks who have never used a power tool of any kind. The point is that coming in to the process with no preconceived notions can be a strength or weakness depending on the individual's personality and attitude.

Too much and too little experience tends to be a liability with the latter unable to confidently use the tools and the former having a harder time taking direction. The sweet spot in the competent but humble student. The way to get the most out of a workshop is the be as prepared as possible but act as if you are a complete novice. We all have a tendency to want to show our knowledge and competence but that really gets in the way in a class setting. After all you are there to find out how a particular instructor does their process, not to show your skill. The task of evaluating whether or not their process works for you is for you to do later once you have had a chance to digest the experience.

There are a few different philosophies of teaching hands on skills. Ours is the "make and take" method where students learn the process while completely finishing a project. This requires a bit of glossing over of some minute details and usually some hands on help by the instructors but it gives students a good overview of the process and something to show for their efforts. Most people taking classes in the arts or crafts will just do it once for the experience. Think of glass blowing, clay throwing or cutting board making at the local wood shop. Many people think they are embarking on a hobby but decide against it after a class because of the high barrier to entry both in equipment cost and time required.

Another way to do classes is technique teaching in which students learn specific ways of achieving certain details in a craft but don't ultimately finish any one project. This can take the form of workshops where nothing is actually physically made but more commonly the student takes home unfinished projects. The American Bladesmith Society classes are a good example of this. They are more in depth about the particulars of how to build a knife that passes the ABS test requirements but participants do not typically finish any knives over the week long course.

When it comes to the make and take class there are two main variations. One option is to carefully control the design process so that the student project comes out how the instructor intends, the other is the teach the techniques but leave the design to the individual student. In our classes, students finish a knife over the course of either one or two days. The one day class starts with one of our heat treated blanks so the design is limited but in the two day class students forge a knife from scratch. This leaves the design window wide open and this is where things get interesting.

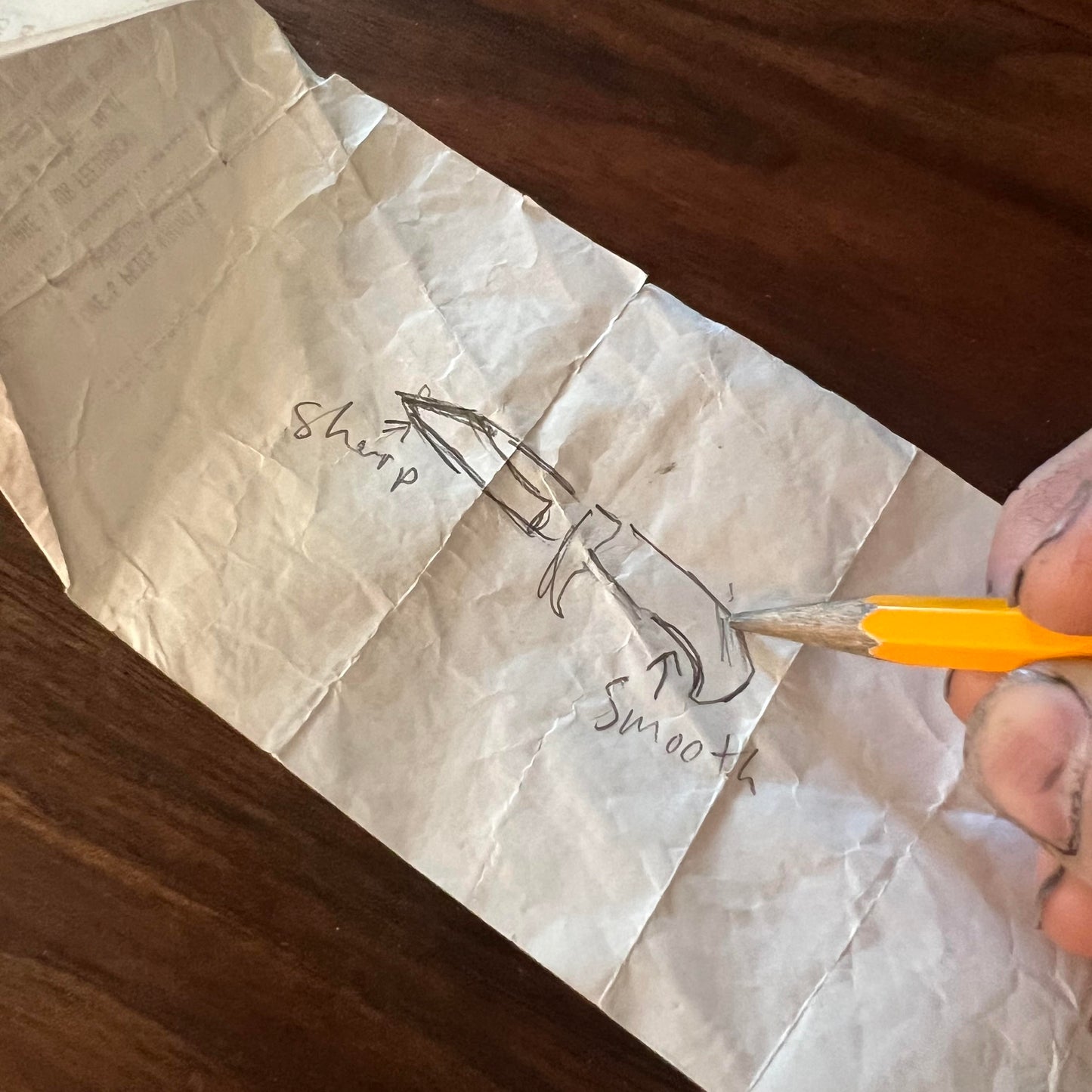

If one looked at al the designs in the world of knives, one will notice that there are more similarities than differences. Many of the same shape and material limitations that were in play during the paleolithic era apply today: Pointy end away from you, grabby end toward you. Not too thick or thin for an average human hand. Blade too thick and it won't cut, too thin and it will break or bend too easily. Most knife makers start out by exploring all kinds of design options, engaging in all kinds of creative shapes but as they gain more experience the designs tend to become limited to more traditional shapes. This is because those traditional shapes are the product of a trial and error process lasting thousands of years and there is just not enough time in a single human lifetime to gain a fraction of that knowledge. This could lead to a much larger conversation of respect for tradition but we will leave that aside for now.

Back to the class attendee that fits in the sweet spot of competence and humility. This is the kind of person that asks for design input and looks at the available examples for inspiration. They don't try to reinvent the knife concept on their first attempt and they don't try to add all the bells and whistles on their first knife either. This leads to a simple project that can be executed well with little experience. The more we stray outside of the basic knife design, the harder it is to achieve a well made project as a new maker. The more levels of complexity added, the more potential points of failure. Jimping, more pins and fasteners than needed, multiple material handles, and even high end handle materials add difficulty that is senseless when trying knife making for the first time. When it comes to technique and materials, get a grip on the simple and functional before incrementally adding layers of complexity.

I will do my best to get each person through our class with a great knife outcome but each student must meet me at the intersection of their ability and their need for instruction.

I took the “Make and Take” knife forging class with Greg Campbell last weekend (7/13/2024). I had a great time and finished with a knife I’m proud of. Greg was a great instructor, allowing us freedom in design but providing guidance and correction as needed. I’m hoping to find a way to make knives on my own in the future. This class gave me the basics I need to start. Thank you!